Hello and welcome to Wooden City, a newsletter about London.

If you haven’t come here via @caffs_not_cafes, I'm a writer called Isaac Rangaswami and this is my Substack.

Every other week I publish an article about everyday places in London with unusual staying power, like shops, buildings, restaurants and public spaces.

In case you missed them, the last fortnightly newsletter was on London’s indoor public spaces, followed by a special companion piece last week.

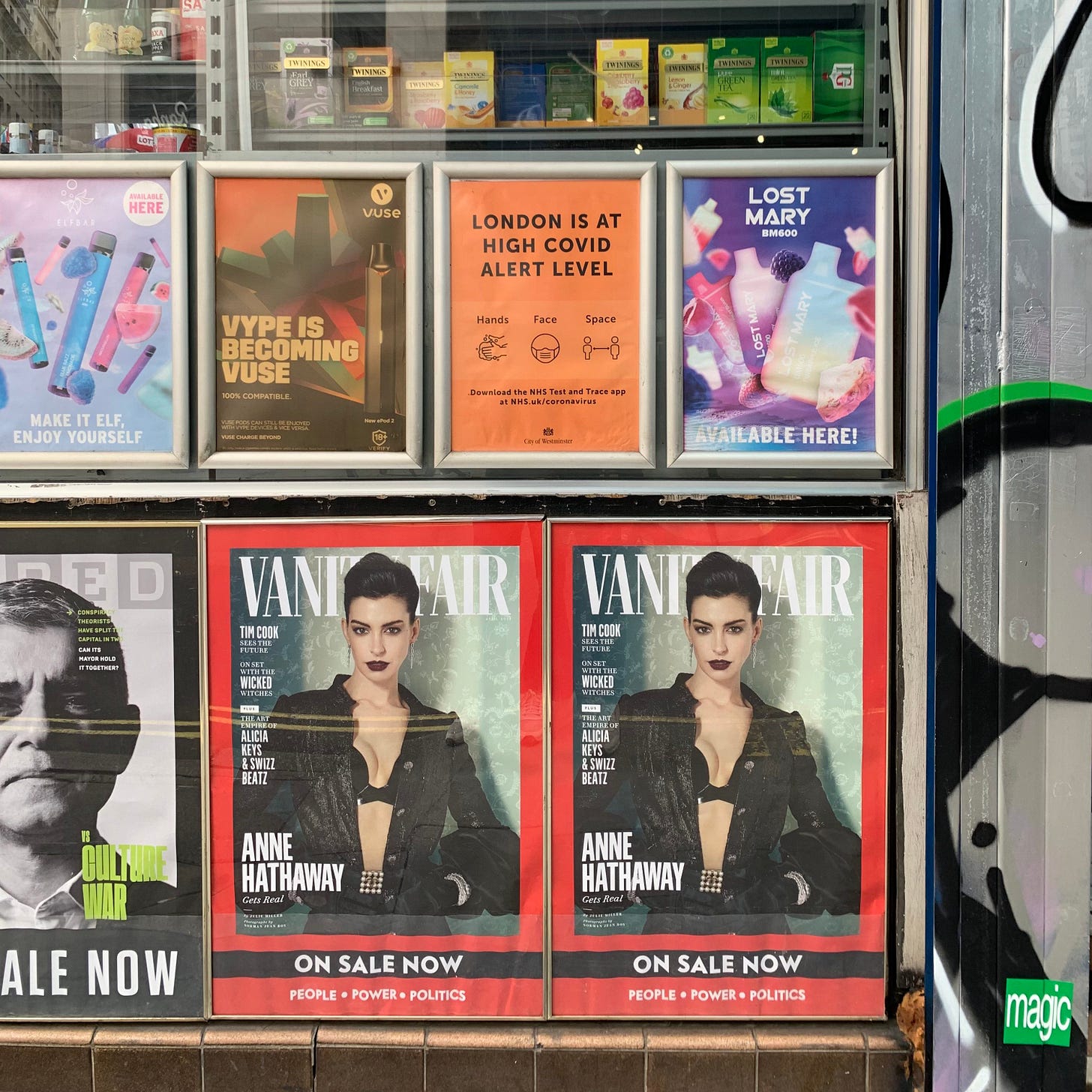

There’s a Soho newsagent I go to sometimes on the corner of Brewer Street and Lower John Street, called One Stop Food & Wine. The other day I noticed something in its window that really shouldn’t be there. Something that should have been covered up years ago, or simply removed.

It is an orange A4 poster that says, “LONDON IS AT HIGH COVID ALERT LEVEL”. It was probably put up in late 2020, and became defunct in varying ways not long after that. This sign may be interesting one day, but the moment literally no one cares.

I like ageing signs – usually ones that are older and more characterful than this one – because they tend to contain these types of clues. The materials used, and whether they are hand-painted, can help you date the place they signpost, whether it still exists or not. They can also help to reveal something about the people who installed them or picked them out. In a restaurant setting, the items on the walls help determine a place’s overall personality, alongside the cutlery, the furniture and the style of the light fixtures.

But as restaurants age, owners tend to destroy these artefacts. I try not to resent this, because the refurbisher’s intentions are usually pure. More so than a mini-cab office or a high street solicitor, hospitality businesses tend to refresh their interiors and shopfronts regularly, to show that they are clean and modern. It’s a commercial decision, rooted in the need to attract and retain customers. Few proprietors, even those who try to evoke nostalgia, want to be seen as genuinely stuck in the past.

What I find interesting about those who preserve oldness, intentionally or otherwise, is how people receive the datedness they create. When an old-fashioned restaurant is well-maintained, its datedness can represent constancy and reliability, and feel quaint and novel when compared to prevailing trends. These factors can even make people overlook average food. But when the signs of ageing are visible and the food is more basic, the opposite can happen. Depending on the place and your way of thinking, dated can just as easily mean dull, dirty and disgusting.

Maybe it’s just me, but I feel like everyone I follow on Instagram is going to Oslo Court in St John’s Wood at the moment, a restaurant which sits firmly within the “good dated” category. I know that writers have been reflecting on its restaurantness for at least 22 years, but it looks to me like a new wave of millennials are getting into it too. My other evidence for this is its high position in Time Out London’s 50 best restaurants list this year, along with Sweetings and Ciao Bella, two other famous anachronisms.

If people really are paying more attention to dated restaurants right now, they have also been drawn to these places for ages. I think dated restaurants have a continuous appeal, which begins as soon as they’re old enough to say something about the past. As they age, they become more important too. This is because others like them continually die out, while those that remain get ever older, making the chasm between old and new more dramatic.

This process, whereby we treasure the last surviving examples of an increasingly rare thing, is exactly how buildings are listed. It is also how nostalgia pulls off its magic trick: staying the same while also becoming more acute. To test this idea further, I’ve been going back to three beautifully dated restaurants, each of which has an enduring appeal. As with my marketplaces piece, I’ve tried to paint a standalone portrait of the people and things that occupy each place, to capture what makes it unique.

Oslo Court

I was a bit nervous about going back to Oslo Court because I feel awkward eating alone in fancy restaurants. At cheaper, or less service-led places, you can be pretty anonymous. When you’re on your own somewhere expensive, where the staff give you more attention, you can feel like you stick out.

But I shouldn’t have worried, because Oslo Court welcomed me with open arms. After reading my name on the booking, the exuberant, hairless man at the entrance designated me “uncle Isaac”, before ushering me in as if I’d been coming for years. He then referred to me as “my gorgeous” and a “lovely person”, as he showed me to a corner table that he had picked out just for me, so that I could enjoy my book in peace and observe everyone else.

It was only later that I discovered this divine being has worked here since 1976. He has been voted Britain’s most-loved waiter and is basically famous for treating people like this. I saw him offer everyone else the same treatment, but I still felt like his favourite, partly because he told me as such. His amiability seemed wholly genuine, honed through decades of trying to make guests feel welcome and ready to enjoy themselves.

Oslo Court is also fun because there’s nowhere else like it. I can’t name the exact colour of its velveteen club chairs, though I think it’s somewhere between cornflower and cerulean blue. It is a rounded, old-world blueness that I don’t think I’ve ever encountered before, that leaps out against the pale pink cloths on the tables. This iconic pinkness actually seems quiet in comparison, as if the tablecloths are only that colour because someone accidentally put a red sock in the white wash.

If it wasn’t for the Muzak, I would also say that Oslo Court sounds like Spandau Ballet. It is a room full of a certain kind of romance and sophistication, once contemporary and now outmoded, that emerged before my parents had me and faded away while I was a child. It is expressed perfectly in the single pink rose that decorates every table, a motif that also features on the sign outside and on the pretty receipt you may choose to retain as a memento.

Crowd-wise, Oslo Court at lunchtime on Wednesday remains a place for glamourous Facebook users. On this visit I noticed slacks, blazers and quarter-zip fleeces; pearls, diamanté and wispy, dyed hair. I heard cockney accents alongside received pronunciation and voices quivering with age. I saw a group of old friends with gin and tonics inspire each other to order the same thing. More than anything, I saw a special occasion restaurant, filled with returning customers happy to be back.

The funny thing about the food is that so much of it is table dressing. I ate some Melba toast and crudités because they were there, before the whole unfinished lot was politely withdrawn. Next I had a plate of asparagus with hand-spooned hollandaise. After that I had the schnitzel Holstein with capers, anchovy twirls and a fried egg, that I also enjoyed and didn’t taste that different from dishes I’ve eaten in caffs. As standard it came with mountains of roasted veg that I’d substitute for something else next time, like cauliflower cheese.

When it was time for dessert, the angel from reception agreed that the apple strudel was a good option, before he said, “I’ll give you something better too, don’t worry,” emphasised with a flick of the wrist. I soon found myself with two doorsteps of strudel and bread pudding, which I ate with tea. I left feeling sleepy, my stomach bursting with bygone food. Yet the whole experience was full of life, too vibrant to be dated. It was more dream-like, or timeless even.

Charlbert Street, London NW8 7EN